Tutorial 2: Geometry and Cameras

- Part 1: Getting required libraries

- Part 2: Creating Objects

- Part 3: Transforming Objects

- Part 4: User Input

- Part 5: Extra

- Note: Using with older OpenGL versions

This tutorial covers how to create an OpenGL camera and simple polygon mesh for rendering. Real-time input will be used to move a virtual camera.

This tutorial will continue on from the last by extending the previously created code. It is assumed that you have created a copy of last tutorial’s code that can be used for the remainder of this one.

Part 1: Getting required libraries

OpenGL or SDL do not provide any mathematics libraries to assist in common host rendering operations. To help make things easier we will use the GLM library. GLM is specifically written to aid OpenGL programs and is designed to use a virtually identical syntax to what is used in GLSL shaders.

-

To start first download the GLM source code.

-

Extract the contents of the GLM glm/glm folder into a folder named “glm” that is accessible by your code (it is suggested to add it to you existing ‘include’ folder).

Part 2: Creating Objects

GLM can be used to create points/vectors and matrices with all the required functions for performing transformations. It is also specifically written for OpenGL interoperability which helps simplify coding.

- Before GLM can be used the appropriate headers must be included. In this tutorial we will use the base GLM functions as well as additional matrix transformation functions. Add the following headers to you code.

// Using GLM and math headers

#include <math.h>

#include <glm/glm.hpp>

#include <glm/gtc/matrix_transform.hpp>

#include <glm/gtx/type_aligned.hpp>

using namespace glm;

In the last tutorial only a single clip space triangle was used for rendering. This is obviously rather limited in its use as it’s much more useful to be able to render full 3-dimensional geometry. To that end the first step is to first create some geometry to render. The simplest of which to start with is a basic cube.

OpenGL supports specifying polygons in various different formats; triangle lists (this was used in the last tutorial – despite having a list length of 1), triangle strips, triangle fans and indexed triangles. The latter of which is the most commonly used as it generally provides the smallest memory footprint by removing vertex duplication. However, it is slightly more involved to create than the other formats as it requires a list of each vertex as well as a list of indexes. This index list is used to create the final triangles as each group of 3 indexes in the index list is used to reference 3 vertices in the vertex list to create a triangle (where index 0 refers to the first triangle in the vertex list, index 1 refers to the next and so forth).

- We must first create some geometry to render. To do this we must create a function that will generate the required geometry for us. This function will take as inputs 2 already created buffers that are used to store the vertex list (vertex buffer) and the index list (index buffer) respectively. The function will add the created geometry to the passed input buffers and then return the number of indexes in the index buffer (this is needed for rendering).

struct CustomVertex

{

vec3 v3Position;

};

GLsizei GL_GenerateCube(GLuint uiVBO, GLuint uiIBO)

{

// *** Add geometry code here ***

}

- Inside the generate cube function we must now add the code to create the geometry. As we will use transforms to move/rotate/scale the cube all we need to do is build a basic cube in “Model” space. This cube will be a unit cube (length of 1) with its centre located at the origin. The vertices can therefore be created manually. A cube only has 8 vertices that need to be created so the vertex list only needs 8 elements. We will use one of the GLM vector types to store each vertex.

CustomVertex VertexData[] = {

{ vec3(0.5f, 0.5f, -0.5f) },

{ vec3(0.5f, -0.5f, -0.5f) },

{ vec3(-0.5f, -0.5f, -0.5f) },

{ vec3(-0.5f, 0.5f, -0.5f) },

{ vec3(-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.5f) },

{ vec3(-0.5f, 0.5f, 0.5f) },

{ vec3(0.5f, -0.5f, 0.5f) },

{ vec3(0.5f, 0.5f, 0.5f) }

};

- Next the indices must be created. This requires indexing into the vertex list and creating each triangle one at a time. A cube has 6 faces each of which should be created using 2 triangles. This then requires 12 triangles each with 3 vertices for a total of 36 indexes. Care must be taken to ensure that each triangle has the correct rotation (clock-wise for front facing) when viewed from the outside of the cube so that the triangles are not culled by the back-face culling stage.

GLuint uiIndexData[] = {

0, 1, 3, 3, 1, 2, // Create back face

3, 2, 5, 5, 2, 4, // Create left face

1, 6, 2, 2, 6, 4, // Create bottom face

5, 4, 7, 7, 4, 6, // Create front face

7, 6, 0, 0, 6, 1, // Create right face

7, 0, 5, 5, 0, 3 // Create top face

};

- Lastly the generate cube function must then load the vertices into the passed in vertex buffer object. The same must be done for the index buffer. However, as this is an index buffer and not a vertex buffer it must be bound using the

GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFERtype. Copying data into the buffer is the same as from last tutorial whereglBufferDatais used by passing the data and its size. So, the only remaining step is to specify the layout of the data in the vertex buffer usingglVertexAttribPointer. This occurs much like last tutorial except now we are passing avec3instead of 2 floats.

// Fill Vertex Buffer Object

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiVBO);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeof(VertexData), VertexData, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

// Fill Index Buffer Object

glBindBuffer(GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiIBO);

glBufferData(GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeof(uiIndexData), uiIndexData, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

// Specify location of data within buffer

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 3, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(CustomVertex), (const GLvoid *)0);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(0);

return (sizeof(uiIndexData) / sizeof(GLuint));

Cubes are rather simple and easy to implement. A slightly more complicated basic shape is the sphere. Spheres are harder to represent using polygons as triangles cannot represent curved surfaces exactly. Instead, they have a level of tessellation depending on just how many triangles are used to create the sphere. The more triangles the smoother the sphere looks. However, the more triangles the more complex the sphere becomes. To allow for the tessellation of the sphere to be altered the sphere should be created dynamically by specifying the number of vertices around the sphere horizontally (u) and the number of vertices used vertically (v).

- Much like the function to create a cube a function to create a sphere must be made. However, unlike the cube function this one requires the tessellation values for u and v to be passed as well.

GLsizei GL_GenerateSphere(uint32_t uiTessU, uint32_t uiTessV, GLuint uiVBO, GLuint uiIBO)

{

// *** Add geometry code here ***

}

As the tessellation of a surface requires 2 parameters used to map to the surface (u, v), the easiest way to generate a sphere is to use spherical coordinates. In spherical coordinates we control the horizontal step (u direction) around the surface by varying the value of theta (θ) and we can control the vertical sweep (v direction) by varying the value of phi (φ). In spherical coordinates where theta sweeps through the x-z plane:

\[x = r\cos\theta\sin\phi\] \[y = r\cos\phi\] \[z = r\sin\theta\cos\phi\]Each tessellation value represents the number of segments the surface needs to be broken into along the horizontal (TessU) and vertical directions (TessV). This requires determining the angle to rotate around each axis (dTheta, dPhi) in order to create each vertex. Once determined we can then generate the first vertex and then continually increment the value of θ from 0 all the way round to 360. We can then continuously increment φ from 0 to 180 after each new horizontal row has been created in order to create all the vertices. This however will create duplicated vertices at the very top and bottom point of the sphere as these points are shared with all the triangles at the top and bottom of the sphere respectively. The number of created vertices can be reduced by sharing this vertex and only creating it once. This will reduce the number of vertices required by TessU-2.

- The first step to create a sphere mesh is to determine the number of vertices required. This is TessU multiplied by TessV minus the number of shared vertices at the top and bottom (TessU-2). The number of indexes is equal to the number of faces (TessU x TessV) times 6 (as there are 2 triangles per face) less the number of faces in the top and bottom as these are created as single triangles that share the top/bottom vertex (TessU x 2). The additional number of indexes at the top and bottom equals the tessellation TessU x 3 vertices per triangle multiplied by 2 (for the top and bottom). dTheta and dPhi are then calculated by dividing the total possible range of each angle (360 for horizontal and 180 vertical) by the number of steps (the tessellation value).

// Init params

float fDPhi = (float)M_PI / (float)uiTessV;

float fDTheta = (float)(M_PI + M_PI) / (float)uiTessU;

// Determine required parameters

uint32_t uiNumVertices = (uiTessU * (uiTessV - 1)) + 2;

uint32_t uiNumIndices = (uiTessU * 6) + (uiTessU * (uiTessV - 2) * 6);

// Create the new primitive

CustomVertex * p_VBuffer = (CustomVertex *)malloc(uiNumVertices * sizeof(CustomVertex));

GLuint * p_IBuffer = (GLuint *)malloc(uiNumIndices * sizeof(GLuint));

- The first step to create the sphere is to generate the top and bottom shared vertex. This vertex will be the first and the last to be stored in the vertex buffer and will be located at ±1 along the y-axis.

// Set the top and bottom vertex and reuse

CustomVertex * p_vBuffer = p_VBuffer;

p_vBuffer->v3Position = vec3(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f);

p_vBuffer[uiNumVertices - 1].v3Position = vec3(0.0f, -1.0f, 0.0f);

p_vBuffer++;

- The reminder of the vertices can then be created by looping over each tessellation step and creating the vertices. This can be done by first looping over each θ value and then looping over the φ values.

float fPhi = fDPhi;

for (uint32_t uiPhi = 0; uiPhi < uiTessV - 1; uiPhi++) {

// Calculate initial value

float fRSinPhi = sinf(fPhi);

float fRCosPhi = cosf(fPhi);

float fY = fRCosPhi;

float fTheta = 0.0f;

for (uint32_t uiTheta = 0; uiTheta < uiTessU; uiTheta++) {

// Calculate positions

float fCosTheta = cosf(fTheta);

float fSinTheta = sinf(fTheta);

// Determine position

float fX = fRSinPhi * fCosTheta;

float fZ = fRSinPhi * fSinTheta;

// Create vertex

p_vBuffer->v3Position = vec3(fX, fY, fZ);

p_vBuffer++;

fTheta += fDTheta;

}

fPhi += fDPhi;

}

- The indexes are created in 3 steps. The first step is to create each triangle around the top of the sphere. These triangles all share the same top vertex with the remainder of the vertices being those created by the first arc around θ. Care must be taken as the last triangle should loop back around to the start.

// Create top

GLuint * p_iBuffer = p_IBuffer;

for (GLuint j = 1; j <= uiTessU; j++) {

// Top triangles all share same vertex point at pos 0

*p_iBuffer++ = 0;

// Loop back to start if required

*p_iBuffer++ = ((j + 1) > uiTessU) ? 1 : j + 1;

*p_iBuffer++ = j;

}

- The remainder of the triangles can be created by looping around each value of θ and then each value of φ and creating the required faces. Each of the faces consists of 2 triangles and again the final face will share vertices with the first as it loops back to the beginning.

// Create inner triangles

for (GLuint i = 0; i < uiTessV - 2; i++) {

for (GLuint j = 1; j <= uiTessU; j++) {

// Create indexes for each quad face (pair of triangles)

*p_iBuffer++ = j + (i * uiTessU);

// Loop back to start if required

GLuint Index = ((j + 1) > uiTessU) ? 1 : j + 1;

*p_iBuffer++ = Index + (i * uiTessU);

*p_iBuffer++ = j + ((i + 1) * uiTessU);

*p_iBuffer = *(p_iBuffer - 2);

p_iBuffer++;

// Loop back to start if required

*p_iBuffer++ = Index + ((i + 1) * uiTessU);

*p_iBuffer = *(p_iBuffer - 3);

p_iBuffer++;

}

}

- The last step is to create all the triangles that share vertices with the bottom point. This is created much like those for the top point except they are offset by the number of shared vertices from top and bottom (TessU-2).

// Create bottom

for (GLuint j = 1; j <= uiTessU; j++) {

// Bottom triangles all share same vertex at uiNumVertices-1

*p_iBuffer++ = j + ((uiTessV - 2) * uiTessU);

// Loop back to start if required

GLuint Index = ((j + 1) > uiTessU) ? 1 : j + 1;

*p_iBuffer++ = Index + ((uiTessV - 2) * uiTessU);

*p_iBuffer++ = uiNumVertices - 1;

}

- Once all the lists have been created, they need to be loaded into the passed in OpenGL buffer objects. The number of indices in the index buffer is then returned.

// Fill Vertex Buffer Object

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiVBO);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiNumVertices * sizeof(CustomVertex), p_VBuffer, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

// Fill Index Buffer Object

glBindBuffer(GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiIBO);

glBufferData(GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, uiNumIndices * sizeof(GLuint), p_IBuffer, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

// Cleanup allocated data

free(p_VBuffer);

free(p_IBuffer);

// Specify location of data within buffer

glVertexAttribPointer(0, 3, GL_FLOAT, GL_FALSE, sizeof(CustomVertex), (const GLvoid *)0);

glEnableVertexAttribArray(0);

return uiNumIndices;

Part 3: Transforming Objects

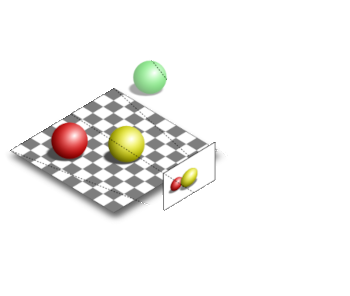

Transforming objects is accomplished by rendering each object with a transform associated with it. The renderer will then transform the object during rendering. We can take advantage of that by rendering multiple objects using different transforms. Each of these objects can be rendered using the same mesh but just with different transformations. This reduces memory requirements as multiple meshes can be rendered using the same vertex and index buffers.

Each object will then have 2 transformations applied to it. The first is its “Model” transformation that transforms the object from its own “Model space” that it was created in and places it at the correct location within the “World” space. The second transform is the camera transformation. This transformation is used to transform each object according to the cameras current view and projection values (“ViewProjection”). Each of these 2 transforms should be passed to the renderer separately. This allows for the objects “Model” transformation to be updated independently of the camera and vice versa. This provides the ability for each to be independently controlled. Although it is possible to combine these 2 transformations and send that to the renderer it is often faster to allow the render hardware to perform this operation as it is capable of doing many such operations concurrently and is often faster than performing them individually on the host computer.

To transform an object, the renderer needs the transformation to be applied to be passed to it. OpenGL supports the concept of a Uniform Buffer Object (UBO). A UBO is a section of data stored within the renderer that can be used to pass data to shader programs. UBOs have the advantage that they are persistent within the renderer’s memory so they only need to be updated whenever a value is actually changed. Since they reside within the renderer it is also very quick to swap between them as no memory copy operation needs to be performed as it’s simply a matter of updating the current state to refer to the required UBO. UBOs function similarly to vertex or index buffers except that they can be used to store any data required including passing transformation data.

Once created uniform buffers need to be mapped to the inputs of a shader program. This first requires probing the shader program in order to get the OpenGL ID of the associated input and then binding the UBO data to that input. UBOs simplify that task by providing binding locations which can be used to create a link between the shader input and a UBO ID. This works by first determining the ID of the shader programs associated input. This input can then be linked to an arbitrary binding location using a user specified binding ID. Using newer OpenGL version this can be specified directly in the shader code by explicitly giving a shader input a binding ID. UBOs can then be bound directly to the binding location which creates the link between the UBO and the shader input. This allows for custom binding locations to be created that each link to the shader program however the user desires.

- The vertex shader needs to be updated to support passing the 2 transformations. The shader also needs to be updated so that the input vertex is passed as a

vec3(last tutorial used avec2to pass the 2D clip coordinates). UBOs are passed to shader programs using nameduniformblocks. Each of these blocks is similar to astructin that they can contain multiple different data elements. Here however we are only passing a single 4x4 matrix so we will use the GLSL inbuilt typemat4within the transform blocks. We must create 2 UBO blocks; 1 for the object transform (TransformData) and 1 for the cameras transform (CameraData). Each block must have a unique name used to identify it. We uselayout(binding)to explicitly specify the binding location of each block which will later be used to bind a UBO to each shader input (here the transform data is at binding ‘0’ and the camera is at binding ‘1’). Each data element within a block is made available globally so each of these must also have a unique name. This unique name can be used to directly access eachmat4to transform the vertex in order “Model” followed by “ViewProjection”.

#version 430 core

layout(binding = 0) uniform TransformData {

mat4 m4Transform;

};

layout(binding = 1) uniform CameraData {

mat4 m4ViewProjection;

};

layout(location = 0) in vec3 v3VertexPos;

void main()

{

gl_Position = m4ViewProjection * (m4Transform * vec4(v3VertexPos, 1.0f));

}

- We have created 2 functions to generate both a sphere and a cube. Each of these will be used to create a vertex and index buffer. To do this we will need 2 OpenGL IDs for each buffer and a Vertex Array Object (VAO) used to store all the buffer values respectively. We also need the number of indexes created in each index buffer as this is required later for rendering. The number for the cube is always fixed at 36 so this can be omitted and hardcoded later. However, as the sphere tessellation can be changed the resultant number of indices will change as well. This code should replace any equivalent code from the previous tutorial.

GLuint g_uiVAO[2];

GLuint g_uiVBO[2];

GLuint g_uiIBO[2];

GLsizei g_iSphereElements;

- Now that there are 2 of each of the VAOs and buffer objects we need to create twice as many. Since the buffer creation functions take an input parameter that specifies the number of buffers created then we can extend the existing buffer creation calls to create multiple buffers. The following changes should be made to the

GL_Initfunction.

// Create Vertex Array Objects

glGenVertexArrays(2, &g_uiVAO[0]);

// Create VBO and IBOs

glGenBuffers(2, &g_uiVBO[0]);

glGenBuffers(2, &g_uiIBO[0]);

- To create the cube, the associated VAO must first be bound. The function to fill the cube vertex and index buffers can then be called. Since this generation function will bind both the buffers when it loads the data then these buffers will automatically be bound to the VAO (as we just set it as the current).

// Bind the Cube VAO

glBindVertexArray(g_uiVAO[0]);

// Create Cube VBO and IBO data

GL_GenerateCube(g_uiVBO[0], g_uiIBO[0]);

- Creation of the sphere works almost identically except we use the

GL_GenerateSpherefunction and this time we store the returned number of indices.

// Bind the Sphere VAO

glBindVertexArray(g_uiVAO[1]);

// Create Sphere VBO and IBO data

g_iSphereElements = GL_GenerateSphere(12, 6, g_uiVBO[1], g_uiIBO[1]);

- To create and pass transformations to the renderer we must first create local storage to store these transformations. To do this we can use the

mat4type to store a matrix transformation. We then need an OpenGL ID for each associated UBO used to pass the matrix transforms to the renderer. We will create 5 different transformations.

mat4 g_m4Transform[5];

GLuint g_uiTransformUBO[5];

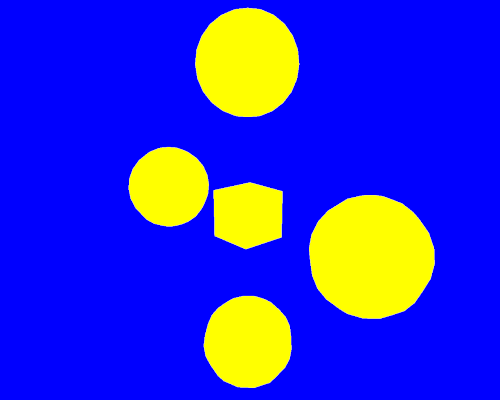

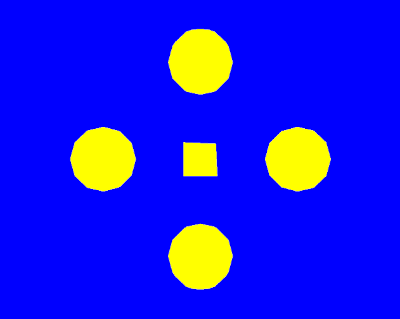

- To create the local transform matrices, code needs to be added to the initialisation function. We will set each of the 5 transforms in order to create a star shape so that the first object is located at the origin and each of the other 4 objects is offset in either the positive or negative ‘x’ or ‘y’ direction. An Identity matrix can be created by using

mat4( 1.0f )and thetranslatefunction can be used to translate an input matrix (here we just use the identity matrix) by an input vector.

// Create initial model transforms

g_m4Transform[0] = mat4(1.0f); //Identity matrix

g_m4Transform[1] = translate(mat4(1.0f), vec3(-3.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f));

g_m4Transform[2] = translate(mat4(1.0f), vec3(0.0f, -3.0f, 0.0f));

g_m4Transform[3] = translate(mat4(1.0f), vec3(3.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f));

g_m4Transform[4] = translate(mat4(1.0f), vec3(0.0f, 3.0f, 0.0f));

- Once the transforms have been created the UBOs need to be created and the UBO data set accordingly. UBOs are created much like any previously used buffer. The only difference is they are bound differently by using the

GL_UNIFORM_BUFFERtype instead. Once bound the data can be copied usingglBufferDataas normal.

// Create transform UBOs

glGenBuffers(5, &g_uiTransformUBO[0]);

// Initialise the transform buffers

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

glBindBuffer(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, g_uiTransformUBO[i]);

glBufferData(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, sizeof(mat4), &g_m4Transform[i], GL_STATIC_DRAW);

}

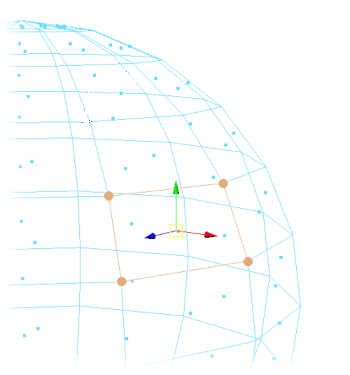

A camera transform can be generated from 2 different matrices; these are the view matrix and the projection matrix. The view matrix is derived from the virtual cameras current position and orientation where the orientation is defined by 3 vectors defining the cameras coordinate system axis (or in other words a vector pointing along the direction the camera is currently looking, a vector pointing to the cameras right and a vector pointing in the cameras up direction).

A First-Person Shooter (FPS) style camera can be created by treating the cameras view in spherical coordinates where θ is used to look left-right φ and is used to look up-down. The camera’s view, right and up direction vectors can then be calculated from these 2 angles. Moving the camera then just requires adding the view direction vector to move forward and right direction vector to move sideways. An FPS camera can therefore de defined by 2 angles and a position. These values can then be used to generate the cameras view matrix. Although it is possible to generate the view matrix at first and then just rotate/translate it as required, this can cause the matrix to become degenerate due to combined floating point errors over time. For simplicity, the matrix can just be regenerated from the input angles avoiding any such issues.

The final camera matrix is the projection matrix. This matrix defines the projective warping applied to the cameras view. This warping can be used to create a perspective warping or in extreme cases a fish eye effect. The most commonly used warping is a perspective-based projection matrix as this simulates the perspective effect found in the human visual system. A perspective projection is defined by the Field Of View (FOV) which is the angle of the perspective effect, the aspect ratio which is used to make sure the perspective effect is correct with respect to the camera’s viewport width and height (which generally corresponds to the window/screen width and height) and the near and far clipping planes. The near and far clipping planes are used to specify the range in which triangles are considered in view.

Any triangle closer than the near plane or further than the far plane will not be rendered. At first it may seem that simply making the near value 0 and then the far value as large as possible would be the best solution. However, the distance between the near and far plane is very important. The renderer only has a limited resolution to represent the entire depth range (this tutorial specified 24 bits during window creation) so if the depth range is larger than required then this just results in decreased resolution in the areas that need it. For best quality, the near and far plane should be set to optimum values for the size of all the geometry being rendered.

- A camera can be defined by 2 angles (AngleX for θ and AngleY for φ) and a position that need to be stored. We will also store the cameras calculated view and right directions (up does not need to be stored as this can be calculated from the cross product of right with view directions). It also needs the projection values for FOV, aspect ratio and near and far plane. Note: It is possible to pre-calculate the projection matrix once as generally its values never change. However, in this tutorial we will allow the projection coefficients to change at runtime which will require the projection matrix to be constantly recalculated anyway.

struct LocalCameraData

{

float m_fAngleX;

float m_fAngleY;

vec3 m_v3Position;

vec3 m_v3Direction;

vec3 m_v3Right;

float m_fFOV;

float m_fAspect;

float m_fNear;

float m_fFar;

};

LocalCameraData g_CameraData;

GLuint g_uiCameraUBO;

- In the initialisation function, we must add initial values for each of the camera’s member data. For this tutorial, we will give it an initial position 12 units down the z-axis and looking back at the origin (θ=π). This corresponds to a view direction looking along the negative z-axis and a right direction parallel to the positive x-axis. These values can be calculated however for simplicity we will simply manually specify these directions for the moment. Note: that should you change any of the camera’s angles then the direction and right vector should also be updated accordingly. We will also initialise the projection coefficients by setting a default FOV of 45°, the aspect ratio based on the current screen width and height, and near and far values of 0.1 and 100 respectively. Although the current scene contents do not extend past 100 by using this value it gives some additional range for the camera position to move about.

// Initialise camera data

g_CameraData.m_fAngleX = (float)M_PI;

g_CameraData.m_fAngleY = 0.0f;

g_CameraData.m_v3Position = vec3(0.0f, 0.0f, 12.0f);

g_CameraData.m_v3Direction = vec3(0.0f, 0.0f, -1.0f);

g_CameraData.m_v3Right = vec3(1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f);

// Initialise camera projection values

g_CameraData.m_fFOV = radians(45.0f);

g_CameraData.m_fAspect = (float)g_iWindowWidth / (float)g_iWindowHeight;

g_CameraData.m_fNear = 0.1f;

g_CameraData.m_fFar = 100.0f;

- Next, we need to generate the cameras UBO. This is exactly the same as the last UBO creation. The GLM function

lookAtcan then be used to create the cameras view matrix and the functionperspectivecan be used to determine the perspective projection matrix. These 2 matrices can then be combined to form the “ViewProjection” matrix that can be loaded into the UBO by binding it withglBindBufferand then loading in the matrix data withglBufferData. Since we are using GLM to create the matrices we don’t have to worry about formatting differences between OpenGL and the host code so we can just directly copy the data. As we wish to be able to update the camera each frame, we use a usage hint ofGL_DYNAMIC_DRAWwhich tells OpenGL that this data will be set once this frame but used many times as it is required for each objects draw call.

// Create updated camera View matrix

mat4 m4View = lookAt(

g_CameraData.m_v3Position,

g_CameraData.m_v3Position + g_CameraData.m_v3Direction,

cross(g_CameraData.m_v3Right, g_CameraData.m_v3Direction)

);

// Create updated camera projection matrix

mat4 m4Projection = perspective(

g_CameraData.m_fFOV,

g_CameraData.m_fAspect,

g_CameraData.m_fNear, g_CameraData.m_fFar

);

// Create updated ViewProjection matrix

mat4 m4ViewProjection = m4Projection * m4View;

// Update the camera buffer

glBindBuffer(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, g_uiCameraUBO);

glBufferData(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, sizeof(mat4), &m4ViewProjection, GL_DYNAMIC_DRAW);

- Since there is only 1 camera UBO, unlike the object transform data the camera data UBO can be bound directly to the binding point now. In the shader code we explicitly set the camera data to use the binding location ‘1’ so now we need to just connect our camera UBO to the correct binding location. This can be done by using the function

glBindBufferBaseto bind the binding point ‘1’ with the cameras UBO OpenGL ID.

// Bind camera UBO

glBindBufferBase(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, 1, g_uiCameraUBO);

- Now all the data has been initialised the objects can be rendered. To do this code must be added to the render function after the shader program has been bound (this replaces any draw calls from the last tutorial). In this tutorial we have 2 different objects we want to render. To render the first object, we need to bind the appropriate VAO in order to set up the required vertex and index buffer data. After that we then need to bind the appropriate transform UBO to the “Model” space transform binding point (previously we set this to binding point 0). After which we need to draw the geometry. As we have used indexed triangle buffers, we must use the

glDrawElementsfunction to draw them. This function draws the vertices in the currently boundGL_ARRAY_BUFFERbuffer and then uses the indexes in the boundGL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFERbuffer. The number of indexes in the index buffer must be passed as the second input to theglDrawElementsfunction. The remaining inputs are the type used to store the indexes (we used standard unsigned integer – unsigned shorts, bytes or long integers can also be used) and the offset into the buffer to start from (here we start at the beginning i.e. 0).

// Specify Cube VAO

glBindVertexArray(g_uiVAO[0]);

// Bind the Transform UBO

glBindBufferBase(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, 0, g_uiTransformUBO[0]);

// Draw the Cube

glDrawElements(GL_TRIANGLES, 36, GL_UNSIGNED_INT, 0);

- Next the spheres can be rendered. This is the same as the above cube code as all we need to do is bind the correct VAO to setup the geometry buffers. However, as we are drawing more than one sphere, we need to loop through all the remaining transform UBOs and bind them to the appropriate binding point before calling

glDrawElementsto draw the sphere.

// Specify Sphere VAO

glBindVertexArray(g_uiVAO[1]);

// Render each sphere

for (int i = 1; i < 5; i++) {

// Bind the Transform UBO

glBindBufferBase(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, 0, g_uiTransformUBO[i]);

// Draw the Sphere

glDrawElements(GL_TRIANGLES, g_iSphereElements, GL_UNSIGNED_INT, 0);

}

- The last requirement is to update the

GL_Quitfunction to correctly delete the additional VAOs and VBOs. We also need to add code for the IBOs as well as for all the UBOs.

// Delete VBOs/IBOs and VAOs

glDeleteBuffers(2, &g_uiVBO[0]);

glDeleteBuffers(2, &g_uiIBO[0]);

glDeleteVertexArrays(2, &g_uiVAO[0]);

// Delete transform and camera UBOs

glDeleteBuffers(5, &g_uiTransformUBO[0]);

glDeleteBuffers(1, &g_uiCameraUBO);

Assuming everything went correctly you should be able to build and run your program at this point and see the cube and 4 spheres displayed correctly.

Part 4: User Input

SDL not only provides OS abstraction for creating windows but it also provides input mechanisms for keyboard and mouse (as well as joystick and controller if desired). These inputs can be used to control the camera to allow it to be moved around throughout the rendered scene. This is done by listening for input events that are triggered by SDL corresponding to an event on either the keyboard or mouse. These events can then be used to move the camera as desired. Doing this however requires knowing the elapsed frame time since the last rendered frame. This is important as any movement in a dynamic system must be scaled by the frame rate (otherwise if things are moved by a constant value each frame, then when run on a computer with a frame rate of 100 things will move 10 times faster than a computer that can only run at 10 frames per second). SDL also provides mechanisms for getting the value from a clock. This value is a constantly updated value so the previous value from the last frame must be subtracted from the current value to get the elapsed time.

- In order to provide real-time updates, we need to determine the elapsed time since the last frame. SDL provides a function

SDL_GetTicksthat can be used to get a value from a system clock. By storing the returned value from last frame (OldTime) we can determine the elapsed time by subtracting it from the current value (CurrentTime). These modifications need to be made to the SDL event loop found in the main function.

...

if (GL_Init()) {

// Initialise elapsed time

Uint32 uiOldTime, uiCurrentTime;

uiCurrentTime = SDL_GetTicks();

// Start the program message pump

SDL_Event Event;

bool bQuit = false;

while (!bQuit) {

// Update elapsed frame time

uiOldTime = uiCurrentTime;

uiCurrentTime = SDL_GetTicks();

float fElapsedTime = (float)(uiCurrentTime - uiOldTime) / 1000.0f;

// Poll SDL for buffered events

while (SDL_PollEvent(&Event)) {

...

- In order to handle all the update calculations, we will create a new function

GL_Updateto handle all of these. This function takes as input the elapsed time and should be placed after the SDL event loop and before the render function is called.

...

}

// Update the Scene

GL_Update(fElapsedTime);

// Render the scene

GL_Render();

...

For an FPS camera the keyboard is generally used to move the camera forward-back or strafe left-right. SDL has events for keyboard presses that have been used previously to detect the ‘Esc’ key. However, with a camera it is generally desirable to allow a button to be pressed and held in order to move the camera. This requires listening for a key pressed event and then moving the camera until such time as the corresponding key released event is detected. It should also be possible for multiple keys to be pressed at once with the combination of these keys creating the resulting movement (holding multiple keys should also cancel each other out if required). This can be achieved by adding movement vectors to the camera. Each time a key is pressed it adds a value to the corresponding movement vector, once the key is released then the added value is then subtracted again.

- In order to support continuous camera movement 2 values must be added to the camera data. These correspond to a forward-back movement vector modifier (MoveZ) and left-right movement modifier (MoveX). These 2 values should be added to the existing camera data structure.

struct LocalCameraData

{

float m_fAngleX;

float m_fAngleY;

float m_fMoveZ;

float m_fMoveX;

vec3 m_v3Position;

...

- Extra values need to be added to the existing SDL event loop to detect additional key press types. Here we will use the standard FPS ‘W’, ‘A’, ‘S’, ‘D’ control scheme. Each time one of these keys is pressed it will increase the corresponding movement vector multiplier (MoveZ or MoveX). For instance, pressing ‘W’ will cause the forward multiplier (MoveZ) to be increased whereas pressing backwards will cause it to be equally decreased. We then need to add an event listener for key release events

SDL_KEYUP. This is similar to the key press events except that the movement vector multipliers are inversed. Since SDL2 has a key repeat ability that only repeats the last pressed key (and therefore is not useable for our purposes) we must ignore any key press events that are repeats of a previously detected one (Event.key.repeat). The value used to modify the movement modifiers (in this case 2.0) is used to change the speed of movement. Increasing/Decreasing these increases/decreases movement speed respectively and can be changed as desired.

if (Event.type == SDL_QUIT)

bQuit = true;

else if ((Event.type == SDL_KEYDOWN) && (Event.key.repeat == 0)) {

if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_ESCAPE)

bQuit = true;

// Update camera movement vector

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_w)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveZ += 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_a)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveX -= 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_s)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveZ -= 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_d)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveX += 2.0f;

} else if ((Event.type == SDL_KEYUP)) {

// Reset camera movement vector

if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_w)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveZ -= 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_a)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveX += 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_s)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveZ += 2.0f;

else if (Event.key.keysym.sym == SDLK_d)

g_CameraData.m_fMoveX -= 2.0f;

}

For a camera the mouse is often used to control the cameras pitch and yaw. SDL provides an event each time the mouse is moved that provides the relative distance along either the screens ‘x’ or ‘y’ axis. This value is represented by the number of pixels that the mouse has moved within the programs window. The window is defined in screen space where (0, 0) is in the top left of the screen and as ‘y’ increases it moves downwards. This requires that the relative ‘y’ value be inverted in order to get appropriate yaw values.

- To get mouse movement input we need to check for an additional event type

SDL_MOUSEMOTION. Unlike with keyboard presses mouse movement is instantaneous and so can be directly applied. We already have 2 existing variables (AngleX, AngleY) that map directly to the mouse movement directions. The relative mouse movement values can be found in the SDL eventsEvent.motion.xrelandEvent.motion.yrelvalues for the horizontal and vertical movement respectively. These values need to then be multiplied by the elapsed time to normalize them and then they are scaled by a fixed amount (in this case 0.05). This value controls the rate of movement and can be changed as desired.

} else if (Event.type == SDL_MOUSEMOTION) {

// Update camera view angles

g_CameraData.m_fAngleX += -0.05f * fElapsedTime * Event.motion.xrel;

// Y Coordinates are in screen space so don't get negated

g_CameraData.m_fAngleY += 0.05f * fElapsedTime * Event.motion.yrel;

}

Once input events have been detected it is the responsibility of the update function to use these values to update the required OpenGL data. The cameras position can be updated by using the movement vector modifiers to modify the cameras position by adding the forward and right vectors respectively. The cameras current and angles are then used to calculate a new view and right direction vector. The cross product of the right and view vectors will then calculate the cameras up vector. These vectors can then be used to generate a new View matrix.

- Now that the input has been detected we can create the implementation of the update

GL_Updatefunction.

void GL_Update(float fElapsedTime)

{

// *** Add update code here ***

}

- The first thing the update function can do is use the cameras movement vector modifiers to update the cameras position. These updates need to be normalised by multiplying them by the elapse time.

// Update the cameras position

g_CameraData.m_v3Position += g_CameraData.m_fMoveZ * fElapsedTime * g_CameraData.m_v3Direction;

g_CameraData.m_v3Position += g_CameraData.m_fMoveX * fElapsedTime * g_CameraData.m_v3Right;

- The cameras yaw (AngleX) and pitch (AngleY) values can now be used to recalculate the cameras view and right direction vectors. Care must be taken to apply each of these rotations in the correct order to avoid unwanted gimbal lock issues. First, we rotate the camera around the global Up vector using the GLM function

rotate. This function takes an existing matrix as input (here we use the identity matrix) and then rotates it by the specified angle (here we use AngleX) around an input direction vector (here we use the global up vector). The global Up vector (0, 1, 0) is used to ensure all yaw rotation occurs around the global axis instead of the local camera Up vector as this causes unwanted rotations in an FPS camera. The resultant matrix is then rotated by the pitch angle using the same GLM function (pitch is rotated around the right (1, 0, 0) direction) to generate a new matrix. This rotation matrix can then be used to transform the global view vector (0, 0, 1) and right vector (-1, 0, 0) to calculate the local cameras view and right vector.

// Determine rotation matrix for camera angles

mat4 m4Rotation = rotate(mat4(1.0f), g_CameraData.m_fAngleX, vec3(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f));

m4Rotation = rotate(m4Rotation, g_CameraData.m_fAngleY, vec3(1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f));

// Determine new view and right vectors

g_CameraData.m_v3Direction = mat3(m4Rotation) * vec3(0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f);

g_CameraData.m_v3Right = mat3(m4Rotation) * vec3(-1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f);

- The camera UBO now needs to be updated. This is the same code as previously used in the initialise function to generate the View matrix using

lookAtand the projection matrix usingperspective. This code as well as the ViewProjection creation and the UBO copy code should now be moved into the update function so that the camera matrix is updated each frame.

- Finally, in order to allow for continuous mouse capture within the program we need to instruct SDL to capture all mouse movement. Without this it would be possible for the mouse pointer to be moved outside the SDL window and for mouse movement capture to be lost. By enforcing mouse capture, we ensure the mouse pointer will never move outside the window. As this may look strange, we will also hide the mouse pointer within the SDL window.

// Set Mouse capture and hide cursor

SDL_ShowCursor(0);

SDL_SetRelativeMouseMode(SDL_TRUE);

The program can now be compiled and run. Assuming everything went correctly you should now have a FPS style camera that can be controlled using keyboard and mouse.

Part 5: Extra

-

Add an additional function that generates geometry for a square pyramid

GL_GeneratePyramid. Create an additional VAO, VBO and IBO to store the pyramid data. Modify your program so that the last 2 objects now use the new pyramid geometry instead of the sphere. -

Notice that should you go directly below the geometry and then look up, any attempt to look left-right results in the camera rolling around the view direction instead. This is a result of gimbal lock due to the initial AngleX rotation being applied to global Up vector instead of the cameras Up vector. However, using the global Up is desired (you can try the same case when using a camera local Up vector – look up and then right then back down and notice the problem). The most common fix for this is to just limit the range the camera can pitch. Modify the camera angle update code to prevent the camera being able to look up-down completely (try limiting it to a 140° total range).

-

Add to the update function so that each objects transform is updated so that the objects now spin in a circle (i.e. the outer objects spin in an arc around the centre object – rotate around z-axis). Since each objects transform is now updated once per frame and used only once to render the corresponding object each frame then the

glBufferDatacall should use the usage hint ofGL_STREAM_DRAWinstead. -

The SDL event

SDL_MOUSEWHEELcan be used to detect mouse wheel events where the eventEvent.motion.xvalue can be used to detect the direction and magnitude of the event (positive values indicate mouse wheel up and negative values for mouse wheel down). Use this event to add extra code that modifies the cameras FOV value. Remember FOV is in radians and input additions should be scaled accordingly. FOV should also have clipping applied to its range to prevent values to small (say less than 10°) or to large (say more than 100°).

Note: Using with older OpenGL versions

This tutorial uses OpenGL functionality that is not found in older versions. For instance, UBO bindings are explicitly specified in shader code using layout( binding ) which is a feature only found in OpenGL 4.2 and beyond. Similar code can still be used on older versions (UBOs are available since version 3.1) by allowing OpenGL to create the binding locations and then manually probing them.

For instance, the current GLSL and host OpenGL code to bind the camera buffer to binding location ‘1’ is:

layout( binding = 1 ) uniform CameraData {

mat4 m4ViewProjection;

};

// Bind camera UBO

glBindBufferBase(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, 1, g_uiCameraUBO);

This can be made compatible with older versions by dropping the use of layout( binding ) and adding host code to setup the binding location. The function glGetUniformBlockIndex can be used to probe a specified shader program for an occurrence of an input block name (here we want CameraData). This function then returns the associated OpenGL ID of that input for the specified shader program. We then use glUniformBlockBinding to link this to a binding location (here we bind it to location 0).

uniform CameraData {

mat4 m4ViewProjection;

};

// Link the camera buffer

uint32_t uiBlockIndex = glGetUniformBlockIndex(g_uiMainProgram, "CameraData");

glUniformBlockBinding(g_uiMainProgram, uiBlockIndex, 1);

// Bind camera UBO

glBindBufferBase(GL_UNIFORM_BUFFER, 1, g_uiCameraUBO);